In planning for the Evaluating Community Impact Community of Practice (Eval CoP), members participated in two summer working group sessions to highlight challenges they faced in their poverty-related evaluation work, and brainstormed topics, content and speakers that could address them. One area that members were greatly interested in learning more about was ‘How to conduct meaningful evaluation in rural settings’.

In planning for the Evaluating Community Impact Community of Practice (Eval CoP), members participated in two summer working group sessions to highlight challenges they faced in their poverty-related evaluation work, and brainstormed topics, content and speakers that could address them. One area that members were greatly interested in learning more about was ‘How to conduct meaningful evaluation in rural settings’.

In response, we invited Dr. Jeannette Waegemakers Schiff, associate professor in the Faculty of Social Work, University of Calgary, to join our September call to share her experiences working on two studies: 'Housing First in Rural Canada' and 'Rural Alberta Homelessness', as well as to share her top tips to more effectively conduct evaluations in rural and remote communities.

Six tips for conducting meaningful evaluation in rural and remote communities

- Account for key contextual factors: Rural and remote is not about only proximity to a metropolitan area, but lies in the context of the questions you are asking. Regional (e.g. economy and industry) and local (e.g. characteristics of homelessness, preparedness for housing first, funds devoted to a given issue), all relate to the purpose of the evaluation.

- TIP: Define a very clear, well-stated purpose, including what you want your outcomes to be. From here, identify key factors that influence them the most, and account for them in designing your evaluation.

- Identify key stakeholders/representative spokespeople, and assess whether a community is ready to engage in change: Political agendas and other factors underlie conversations, and influence what stakeholders’ views are guided by. Look at a community’s history. How tuned in are they to the social/economic needs of its residents? Have they acknowledged that a problem exists and that this is a pertinent issue? As not every community is ready or willing to engage in change, we have to accept that no matter how good an evaluation is, factors such as political feasibility can get an excellent evaluation parked on a back shelf. Conversely, key leadership can move things forward very quickly.

- TIP: Dive deep into a community to identify political dynamics, key stakeholders, their agendas, and where decision-making powers lie. Check for community consistency and/or divisiveness by getting three people in the community to provide answers to a predetermined set of questions. Community members need to be engaged in the discovery progress, and by partnering, they are letting you know that they are ready.

- Incorporate participatory planning and data collection strategies: Evaluation has to be a partnership in the community, and not someone coming in as an outside expert. Participatory strategies allow us to explore the trajectory of change in discovery/emergent conversations and programming. Ultimately, participants will be the biggest proponents in moving things forward once results are disseminated.

- TIP: Work with key leaders and community members to explore what they want to know, and to identify why and how this is meaningful and important. Look closely at skills and talents to engage the community in the efforts you are making, and employ a process that supports them to grow, and to learn more skills for future endeavors. Design evaluations based on their planned audiences and use, have the community establish change markers, and work backwards to find change.

- Address privacy and confidentiality issues: Respondents need to know that information they share will remain confidential.

- TIP: Ethical reviews, clearance and confidentiality statements can serve as important leverage points to have people agree to speak with you.

Obtain rich data that effectively captures nuances of small change: Evaluation in rural/remote communities often generates small datasets, where much time and expense is involved in getting meaningful data, and where formal statistical methods often do not apply.

- TIP: Whenever possible, employ in-person visits, on-site consultation, and employ more than one methodology, including a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods.

- Include the monitoring piece that is too often missing: In programming versus research, the plan we begin with is not what we end up with. Evaluation is still research, just not one employing hypothesis testing.

- TIP: Evaluation needs to begin when the program begins. Establish baselines to allow you to better understand a situation, monitor it, and document movement on an ongoing basis so people can inform and adapt their work along the way. This process is more interactive, meaningful and responsive than waiting for results after a given period of time.

Learn more

- Join the Evaluating Community Impact Community of Practice

- Publication and Webinar: Housing First in Rural Canada: Rural Homelessness & Housing First Feasibility Across 22 Canadian Communities

- Publication: Rural Alberta Homelessness

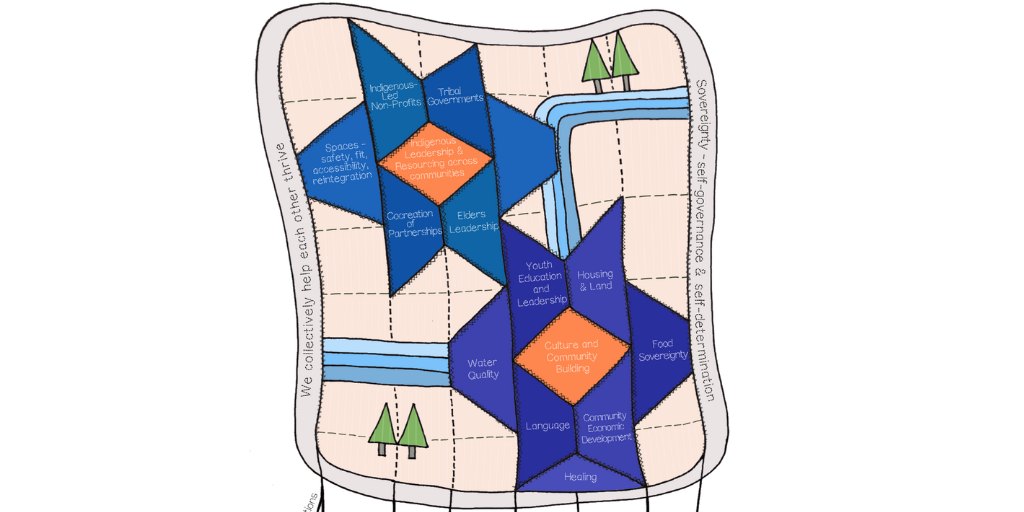

- Article: Rural Aboriginal Homelessness in Canada

- Book: Working with Homeless and Vulnerable People: Basic Skills and Practices