In social innovation we are at risk of confusing our stories of success for real, genuine impact. Without theories, implementation science or evaluation we risk aspiring to travel to the moon, yet leaving our rockets stuck on the launchpad.

There is a Buddhist expression that goes like this:

Be careful not to confuse the finger pointing to the moon for the moon itself. *

It's a wonderful phrase that is playful and yet rich in many meanings. Among the most poignant of these meanings is related to the confusion between representation and reality, something we are starting to see exemplified in the world of social innovation and its related fields like design and systems thinking.

On July 13, 2014 the earth experienced a "supermoon" (captured in the above photograph), named because of its close passage to earth. While it may have seemed also close enough to touch, it was still a distance unfathomable to nearly everyone except a handful on this planet. There was a lot of fingers pointed to the moon that night.

While the moon has held fascination for humans for millennia, it's also worth drawing our attention to the pointing fingers, too.

Pointing fingers

How often do you hear from your colleagues or fellow travellers in the world of social innovation:"we are doing amazing stuff"when hearing about leaders describe their work in the community, universities, government, business or partnerships between them? Thankfully, it's probably a lot more than ever because the world needs good, quality innovative thinking and action. Indeed, judging from the rhetoric at conferences and events and published literature in the academic literature and popular press it seems we are becoming more innovative all the time.

We are changing the world.

...except, that is a largely useless statement on its own, even if well meaning.

Let me explain.

Without documentation of what this "amazing stuff" looks like, a theory or logic explaining how those activities are connected to an outcome and an observed link between it all (i.e., evaluation) there really is no evidence that the world is changed - or at least changed in a manner that is better than had we done something else or nothing at all. That is the tricky part about working with complex systems, particularly large ones.

How the world is changed is subtitle of the the book by Brenda Zimmerman, Frances Westley and Michael Quinn Patton on complexity and evaluation in social change, Getting to Maybe. It is because change requires theory, strategic implementation and evaluation that these three leaders in such topics came together to discuss what can be called social innovation. They introduce theory, strategy and evaluation ideas in the book and -- while the book has remained a popular text -- I rarely see these ideas referred to in my conversations about social innovation.

What is the theory of change? What are the strategies linked to that theory of change and what did it produce? Important questions and the fingers pointing to the moon of real transformation.

Unfortunately, concrete discussion of these three areas -- theory, strategic implementation, and evaluation -- is largely absent from much of the public dialogue on social innovation. No more was this evident than in the social innovation week events held across Canada in May and June of this year as part of a series of gatherings between practitioners, researchers and policy makers from all kinds of different sectors and disciplines. The events brought together some of the leading thinkers, funders, institutes and social labs from around the world and was as close to the "social innovation olympics" as one could get. The stories told were inspirational, the diversity in the programming was wide, and the ideas shared were creative and interesting. the organizers did a fantastic job of bringing the best minds together in a way to share what they did and how they did it.

And yet, many of those I spoke to (including myself) were left with the question: What do I do with any of this? Without something specific to anchor to that question remained unanswered.

Lots of love, not enough (research) power

As often happens, these gatherings serve more as a rallying cry for those working in a sector -- something that is quite important on its own as a critical support mechanism -- but less about challenging ourselves. As Geoff Mulgan from Nesta noted in the closing keynote to the Social Frontiers event in Vancouver (and riffing off Adam Kahane's notion of power and love as a vehicle for social transformation), the week featured a lot of love and not so much expression of power (as in critique).

Reflecting on the social innovation events I've attended, the books and articles I've read, and the conversations I've had in the first six months of 2014 it seems evident that the love is being felt by many, but that it is woefully under-powered (pun intended). The social innovation week events just clustered a lot of this conversation in one week, but it's a sign of a larger trend that emphasizes storytelling independent of the kind of details that one might find at an academic event. Stories can inspire (love), but they rarely guide (power). Adam Kahane is right: we need both to be successful.

The good news is that we are doing love very well and that's a great start. However, we need to start thinking about the power part of that equation.

There is a dearth of quality research in the field of social innovation and relatively little in the way of concrete theory or documented practice to guide anyone new to this area of work. Yes, there are many stories, but these offer little beyond inspiration to follow. It's time to add some guidance and a space for critique to the larger narrative in which these stories are told.

Repeating patterns

What often comes from the Q & A sessions following a presentation of a social innovation initiative are the same answers as 'lessons learned':

- Partnerships and trust are key

- This is very hard work and its all very complex

- Relationships are important

- Get buy-in from stakeholders and bring people together to discuss the issues

- It always takes longer than you think to do things

- It's hard to get and maintain resources

I can't think of a single presentation over the past six months where these weren't presented as 'take-home messages'.

Yet, none of these answers explain what was done in tangible terms, how well it was done, what alternatives exist (if any), what was the rationale for the program and any research/evidence/theory that underpins that logic, and what unintended consequences have emerged from these initiatives and what evaluated outcomes they had besides numbers of participants/events/dollars moved.

We cannot move forward beyond love if we don't find some way to power-up our work.

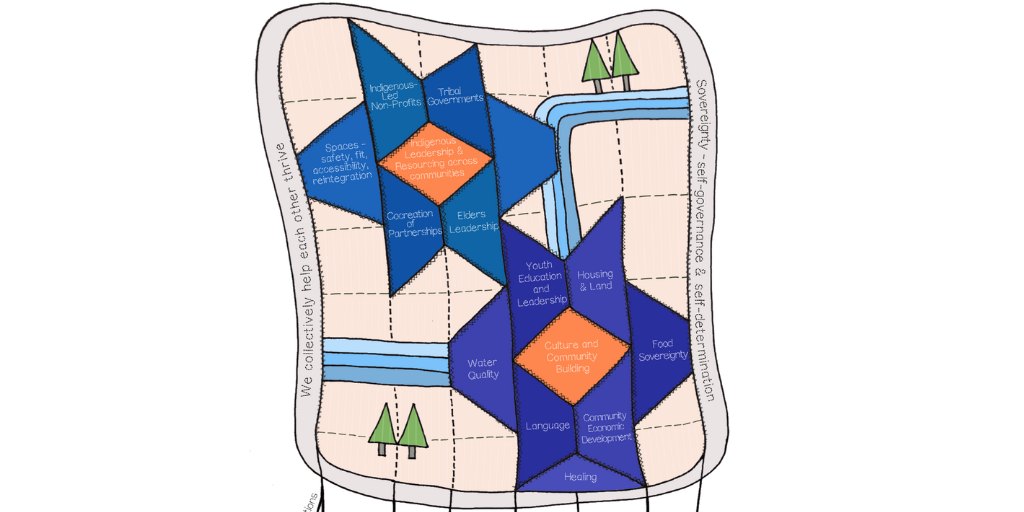

Theories of change: The fingers and the moons

Perhaps the best place to start to remedy this problem of detail is developing a theory of change for social innovation**.

Indeed, the emergence of discourse on theory of change in worlds of social enterprise, innovation and services in recent years has been refreshing. A theory of change is pretty much what it sounds like: a set of interconnected propositions that link ideas to outcomes and the processes that exist between them all. A theory of change answers the question: Why should this idea/program/policy produce (specific) changes?

The strengths of the theory of change movement (as one might call it) is that it is inspiring social innovators to think critically about the logic in their programs at a human scale. More flexible than a program logic model and more detailed than a simple hypothesis, a theory of change can guide strategy and evaluation simultaneously and works well with other social innovation-friendly concepts like developmental evaluation and design.

The weaknesses in the movement is that many theories of change fail to consider what has already been developed. There is an enormous amount of conceptual and empirical work done on behaviour change theories at the individual, organization, community and systems level that can inform a theory of change. Disciplines such as psychology, sociology, political theory, geography and planning, business and organizational behaviour, evolutionary biology and others all have well-researched and developed theories to explain changes in activity. Too often, I see theories developed without knowledge or consideration of such established theories. This is not to say that one must rely on past work (particularly in the innovation space where examples might be few in number), but if a theory is solid and has evidence behind it then it is worth considering. Not all theories are created equal.

It is time for social innovation to start raising the bar for itself and the world it seeks to change. It is time to start advancing theories, strategic implementation and evaluation practice and research so that the social innovation events of the future foster real power for change and not just inspiration and love.

* One of the more cited translated versions of this phrase has been attributed to Thich Nhat Hanh who suggests the Buddha remarked: "just as a finger pointing at the moon is not the moon itself. A thinking person makes use of the finger to see the moon. A person who only looks at the finger and mistakes it for the moon will never see the real moon."

** This actually means many theories of change. A theory of change is program-specific and might be identical to another program and built upon the same foundations as others, but just as a program logic model is unique to each program, so too is a theory of change.