This blog post is the first in a two-part series of posts by Jim Cresswell, PhD, in relation to the COVID 19 and the Newly Vulnerable initiative. Click here to see the second post in this series.

In its 2021 publication titled Communities Ending Poverty: 2021 Progress & COVID-19 Update, the Tamarack Institute noted an unprecedented challenge concerning people referred to as newly vulnerable – those at increased risk due to economic and social pressures linked to the pandemic.

COVID-19 and the Newly Vulnerable project

The Canadian Poverty Institute has been working with Tamarack’s Communities Ending Poverty network to explore the impacts that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on poverty in Canada. The project is called COVID 19 and the Newly Vulnerable.

This work has involved an extensive, cross-Canada survey of over 1,500 participants. The survey was followed by conversations with participants where they were invited to discuss the results, along with best- and worst-case scenarios.

Exploring the results

The disruption of the status quo emerging from the pandemic presented an opportune time to advocate for change in support systems that currently do not account for the newly vulnerable. Capacity emerged as a critical theme.

Increased collaboration

Our results to date have told us that the pandemic unveiled increased creativity between organizations and communities that reshaped collaboration. During the lockdown, communities collaborated in new ways to help community members. Collaboration and creative reshaping of service sector relationships have had lasting positive effects on how organizations structure their programs and services.

Defining our vulnerabilities

The pandemic also made us realize that we are all vulnerable in ways we had not anticipated.

Participants disclosed that a divide between vulnerable and newly vulnerable individuals did not serve any benefits when thinking about both support and systems change.

People who did not hit traditional bureaucratic benchmarks of poverty – who we initially called newly vulnerable – were best understood as people becoming more vulnerable. This was different from thinking about them as a new class or group.

Navigating the system and services

Respondents found that people entering new levels of vulnerability had more skills in navigating systems and therefore better opportunities to access resources and services.

Despite prior relationships with services and service providers, people experiencing marginalization before the pandemic shifted into increased distress and were distanced further from available supports as more people increasingly accessed them. The capacity of the sector to respond was constrained.

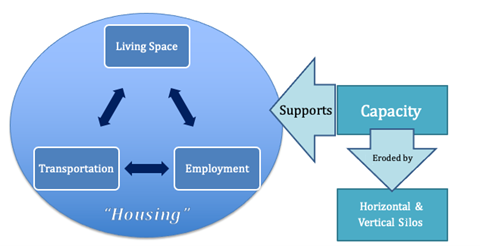

For example, the project highlighted how housing has had a significant impact on vulnerability. Participants revealed that housing did not mean having a place to sleep; it meant having ‘wrap-around’ support, including transportation, employment, and living space.

Understanding capacity

The support for housing increased via capacity. Capacity, in this context, was not the number of services or programs but the ability to sustain relationships and networking among people in supporting agencies.The participants spoke of how people often think about capacity in terms of increased funds and programs. Many participants mentioned that there are funds available and community and private sector partners interested in developing creative solutions. However, the main obstacles were a lack of people who could get the work done and a lack of ability to network.

Respondents told us that people developed initiatives through networking and interpersonal relationships. Capacity was about people and opportunities to relate.

Silos reducing capacity

Vertical and horizontal silos reinforced reductions in capacity.

Vertical silos

Vertical silos occurred when people positioned at higher levels in federal, provincial, territorial and municipal organizations and government could not ‘hear’ the voices of those working with vulnerable persons.

People at different levels saw situations differently and had difficulty communicating. For example, one participant noted that they had many opportunities and ideas but did not have anyone available to capitalize on opportunities by writing grant applications. Those at the provincial level wanted to see the grant application to justify employing a person, creating a paradox that paralyzed the ability to build capacity.

The need to present the current situation of deprivation as the worst possible scenario to those in charge also created vertical silos. Participants described how they had to portray things as ‘really bad’ to get attention from those in power. The scenario made it hard to communicate successes without risking losing the resources necessary to sustain a person's position.

It was apparent to those on the front lines that people and opportunities to network were crucial. Still, these were not obvious to many decision makers – time was spent validating the need for capacity instead of leveraging capacity.

Horizontal silos

Comparatively, some horizontal silos occurred among persons working at grassroots levels due to competition for funding. To support housing, increasing capacity was again the most strategic place to start reducing silos.

For example, more individuals and robust networking could equalize levels in vertical silos and bring organizations together experiencing horizontal silos. If both vertical and horizontal silos in organizations did not change, efforts at poverty reduction would worsen over time, while improvement in capacity would lead to an overall positive change.

Capacity equaled people, relationships, networks and collaboration.

The Meaning of Housing

The relationship between capacity, supports for an issue such as housing, and the perils of horizontal and vertical silos are illustrated in the diagram below.

Join us at the summit

A virtual Action Summit to be held October 3, 2022, will tackle these issues by looking at the data from our follow-up interviews. We will be bringing together project partners to discuss potential actions and initiatives.Registration for the Summit is now open! If you have questions, please send your queries to covidmobilization@ambrose.edu.