This Case Study was written by Susan Foster, Developmental Evaluator and Lisa Attygalle, Consulting Director, Tamarack Institute.

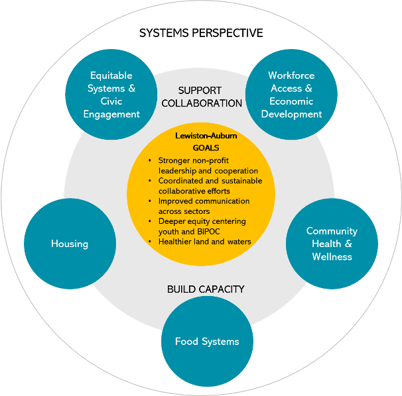

In 2018, the Sewall Foundation initiated a community engagement process in one of its key focus areas, the twin cities of Lewiston and Auburn (LA). Seeking deeper connections with organizations in these communities, the foundation committed resources to community outreach, collective reflection to surface community priorities, and program co-design. The co-design phase (completed in 2020), facilitated by Lisa Attygalle of the Tamarack Institute, brought a group of 11 community leaders selected from diverse backgrounds and sectors together to affirm five priority areas to be addressed via a systems approach: Equitable Civic Systems, Workforce Access and Economic Development, Community Health and Wellness, Healthy Local Food Systems, and Healthy Affordable Housing.

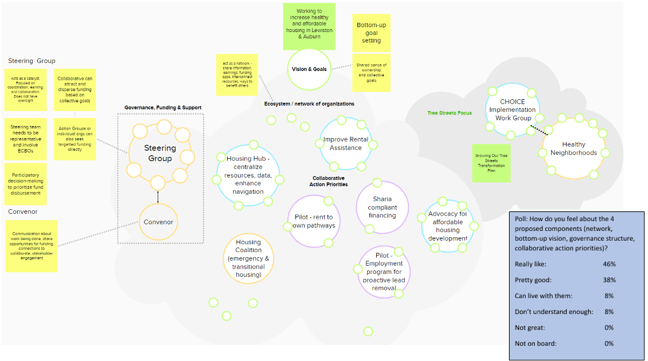

Figure 1: Overview of Systems Approach in LA

Two general strategies would be necessary for systematic impact: to support collaboration and build capacity. The original goals for the LA community engagement process included:

-

Stronger non-profit leadership and collaboration

-

Coordinated and sustainable collaborative efforts

-

Improved communication across sectors

-

Deeper equity (centring youth and BIPOC)

-

Healthier land and waters

A case study describing early activities, community engagement strategies, and learning from the initial phases of the LA process can be found here. Anticipating the pilot phase of the process, participants offered their thoughts on what Sewall needed to pay attention to: people’s lack of time and resources for collaboration and planning; keeping youth at the center of the work; remaining vigilant about power dynamics; and having realistic expectations about organizations’ ability to change systems.

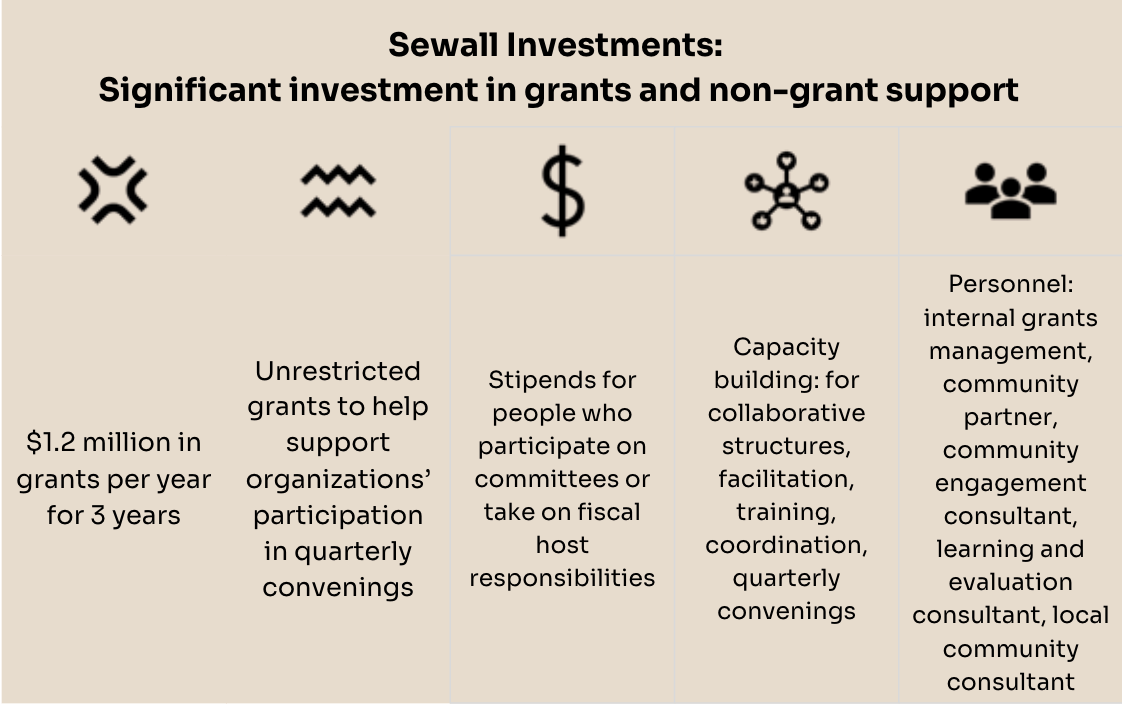

This case study tells the story of the program pilot, which comprised quarterly virtual gatherings of participants across four priority areas, initial participatory grantmaking and non-grant activities, alternative grant reporting, and peer learning.

This case study includes:

-

Participant Perceptions of the Process, Convenings, and Results

-

What the LA Community Engagement Process is Enabling: Early Results

This case study draws from many information sources, including quarterly convening summaries, meeting notes, and a participant survey at the end of the pilot period.

Goals and Line of Sight for Pilot

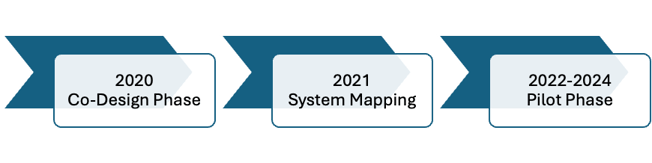

The pilot phase for the LA engagement process ran from 2022 – 2024. A phased approach was recommended by community partners:

The eventual goal should be a community-based decision-making model whereby the community—those affected by the issues and those working alongside them—will decide how available funding will be allocated. But first, some significant power struggles and dynamics among organizations and sectors in L-A need to be addressed. Currently, there is too much competition and not enough trust among organizational leaders (particularly between leaders of mainstream and grassroots organizations). Therefore, in years 1-2, the Co-Design team recommends that Sewall continue to provide unrestricted operating support and program grants directly to organizations and groups whose work aligns with program priorities. Sewall should also support relationship building, collaboration, and capacity building so that by year 3, the community will be ready to transition to community-based decision-making and leadership.

– Co-Design Summary Report, October 2020

Therefore, goals were sequenced, and piloting was built into the process to enable further trust building among LA organizations and to experiment with new ways for the community to make decisions and allocate collective resources.

The planning team—including Lauress Lawrence, Sewall Foundation; Lisa Attygalle, Tamarack Institute; and Susan Foster, Developmental Evaluator—used an emergent learning approach that is suited to collective, complex work. Instead of relying on rigid, pre-planned strategies, it involves making collective thinking visible, framing work as experiments, and continuously learning to adapt and achieve greater impact.

Participants in the LA ecosystem agreed to the following goals:

-

Organizations working together demonstrate greater independence, stronger relationships, an orientation to the collective, and increased shared decision-making.

-

Identifying and resourcing shared initiatives and/or initiatives that meet collective needs.

-

Shifting from Sewall convening to establishing community-led structures for convening, communication, and resource allocation that can be sustained.

-

Developing a network of funders in LA that coordinates their efforts in service of community-led goals.

Activities

Over the three-year pilot period, the following activities took place to work towards shared goals.

YEAR 1: 2022 | BUILDING THE FOUNDATION

Key activities:

-

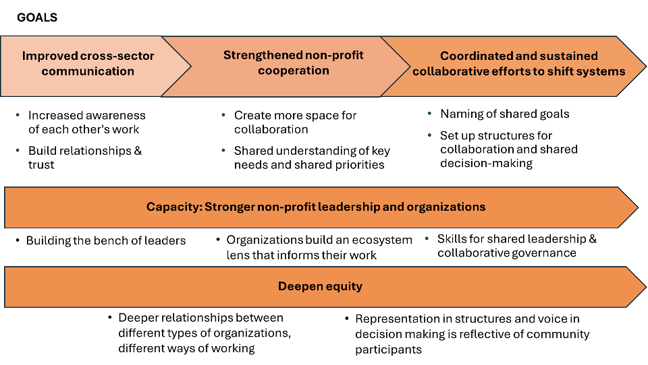

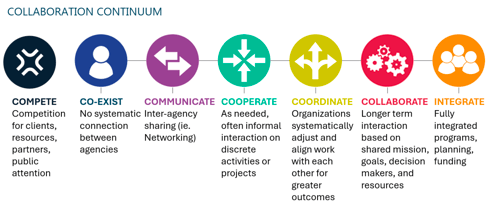

- Within each priority area, community partners reflected on the current state and desired state. They learned about the levels of collaboration and explored what forms of collaboration would help each priority area to reach milestones.

Figure 3: Collaboration Continuum

-

- Explored various governance structures and processes which could enable collaborative action.

-

- Looked at examples to help understand what kind of actions and outcomes are needed to lead to systems change impacts:

-

- Shifting awareness and ownership – including the level of understanding and interest on behalf of local leaders

-

- Nudging systems and policies – including changes to regulations, structures and resource flows

-

- Supporting niche innovations – relating to individual projects, programs, and services

-

-

- Synthesized discussions to determine a collaborative focus for each priority area

-

- Created a draft ecosystem structure and used the Gradients of Agreement as a tool for consensus-based decision making.

Figure 4: Draft ecosystem structure for the Housing focus area in LA

-

- Learned about different formats for participatory grantmaking and designed a process to suit our needs.

-

- Completed quick polling following each session to track levels of trust and contribution.

YEAR 2: 2023 | PRACTICING COLLECTIVE WORK

Key activities:

-

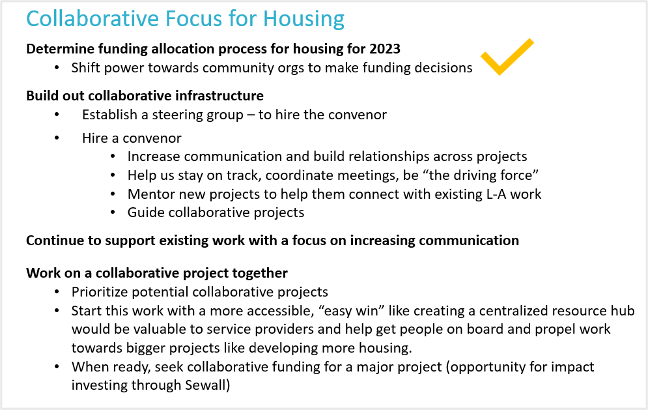

- Implemented a participatory budgeting process to create a budget for each priority area. See an example from the housing priority area.

-

- Confirmed the focus for collaborative work. See examples in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Collaborative focus for housing for the pilot period

-

- Named shared priorities, including priority projects (e.g., transportation pilot) and shared collaborative infrastructure (e.g., convening roles, pooling of funds) and allocated funding to existing partnerships and organizations. Fund allocation decisions were checked against an equity lens. Continued using the Gradients of Agreement as a tool for decision-making.

-

- Created space to build awareness of each other's work and discuss ecosystem needs and opportunities.

-

- Grants were distributed to organizations, partnerships, and fiscal hosts based on participatory allocations.

-

- For priority areas with collaborative infrastructure like convenor roles, steering committees, or pooled funds, we learned best practices in the field and then defined the criteria for roles, representation, and recruiting processes. We discussed ways to increase communication and coordination, and what collective accountability looks like for this work.

-

- In October 2023, a mass shooting in Lewiston brought the community together to provide emergency response and other collective funding to respond to community trauma and healing. A listening session was hosted to understand core needs and learn from the community about how best to issue rapid response funding.

-

Reflected together: End-of-year check-in, recognition of progress, and line of sight to 2030.

YEAR 3: 2024 | BUILDING STRUCTURES AND PROCESSES TO ENABLE COLLECTIVE WORK

Key activities:

-

- Taking stock together: What’s changing in this ecosystem? What do we need to pay attention to this year?

-

- Hosted Shared Learning Sessions as an alternate form of grant reporting. Organizations with Sewall funding were invited to share a slide and describe their work to each other, using 3 prompts:

-

- What is the story behind the picture that you are sharing, and why does it make your organization proud?

-

- What is something that your organization has learned this past year? How has that learning been changing how you work?

-

- What is the main challenge or opportunity you are experiencing now? How can other organizations in LA help you to address that situation?

-

-

- Recruited steering committee members and created group agreements for how they will work together and make decisions.

-

- Launched collective initiatives unique to each priority area. See the next section for more details.

-

- Reflected on progress. Discussed how to resource ourselves differently to allow for a greater focus on larger-scale impact now that processes and structures are formed.

Participant Perceptions of the Process, Convenings, and Results

In late 2024, at the end of the pilot period, we distributed a participant survey that produced 58 responses (26% of all participants), with good distribution across priority areas (Health: 36%; Equity: 17%; Housing: 19%; Workforce: 28%). Those who filled out the survey were very experienced; 42% had been involved for over 3 years, 50% had been involved for 1-3 years, and only 8% had less than 1 year of involvement. Most had been to gatherings, but one-third had also been on a planning group, and over one-fifth had been on a steering committee.

This section of the study synthesizes participant feedback on the community engagement process and its progress toward the community-identified goals depicted in Figure 2.

Overall, participant feedback was very positive, with consistent praise for the diversity of its participants, the facilitator and the quarterly virtual gatherings, for everything they had learned, and for the relationships they had developed with other people serving the Lewiston-Auburn community.

WHO PARTICIPATED

At each stage of this community-engaged process, participants represented a diverse array of ethnic-based community organizations, mainstream organizations, schools, and city agencies. Participation stayed strong throughout the pilot period—Immigrant-led organizations were active in each domain, as were youth-led and youth-serving organizations. Participants self-selected into priority areas, with some attending multiple meetings in one quarter.

A few participants felt that there were key organizations missing from the ecosystem. Suggestions for additional organizations were primarily in housing and senior services. New community partners joined each quarter.

Some people asked for increased emphasis on diversity that goes beyond race and ethnicity, such as LGBTQ+ and people with lived experiences that touch on the community-selected priority areas, to ensure that all people feel that they are relevant to the convenings.

BENEFITS OF PARTICIPATION

People who attended quarterly convenings named multiple ways in which they benefited from being a part of the process. Most mentioned was knowledge sharing across organizations, followed by networking and collaborating, learning from the facilitator about collaborative work, community-based grantmaking, collaborative problem solving, and group facilitation. People’s comments suggested that they made connections that resulted in mutually beneficial collaboration outside of the structured process.

The idea that people are part of the larger system seems to be well understood and enables people to consider what difference they can make, as opposed to the system being something that they cannot influence. The system mapping process (completed just before the pilot period), combined with getting to know each other, enabled people to see where they fit in the system, to share resources and knowledge, and to partner with others to improve the system they work in. Participants said that collaboration strengthened their organizational effectiveness. Consistent funding helped organizations stay involved over time.

RELATIONSHIPS

One of the primary hypotheses driving this community engagement effort has been that by learning from each other, ecosystem members would see where their priorities and missions align and where each organization is uniquely focused, so that collectively they could improve the systems that need to work better for marginalized people. The survey data suggest that most people agreed with statements about curiosity, being welcomed, collaboration, and belonging. Overall, responses were very positive on the quality of their relationships with others in the ecosystem. Some people expressed concern with competition and tension among some BIPOC- and white-led organizations, suggesting that this is an issue for ongoing attention.

QUARTERLY GATHERINGS

A central feature of the community engagement process was quarterly gatherings of each of the four priority areas. Participation at each quarterly meeting included representatives from approximately 15-60 organizations. Overall, people highly valued these sessions. On a scale of 0 (poor) to 100 (great), the average rating was almost 80. Sewall’s decision to hire a facilitator with expertise in community engagement and virtual facilitation was a critical factor in the ability of the ecosystem to advance its goals. The ecosystem facilitator has been instrumental in educating members in facilitative techniques, collaborative structures, and system mapping, giving them the tools they need to identify priorities and to self-govern. She also provided support for newly formed collaborative governing bodies and trained members in community-led budgeting and grantmaking. Members report that they are applying the learning in their own workplaces.

Many people provided written feedback, but the quotes below speak to their learning and increasing connection to others in the group:

“I have learned a lot professionally from the collaborative process, outside-the-box thinking, the thoughtful systems approach put in place around facilitation and inclusion.”

“I have learned a lot about collaborative work, community-determined grant making, and formed valuable connections with others doing incredible work in LA.”

“I’ve enjoyed the camaraderie.”

Although overall ratings were high, people shared some constructive feedback and some ideas for making gatherings even more effective in the future:

-

- Engagement of new members: Newer members seem to need more orientation and support around how they can develop relationships.

-

- Network size and complexity: The network is so large that it is hard for everyone to be an active participant. Size and time constraints make it difficult to hold space for emerging issues, challenges, and cross-pollination of each other’s work. The groups that have not yet matured to a working structure will need continued facilitation assistance to advance their development.

-

- Competition: remains a barrier to progress.

-

- Purpose: Some people struggle with the objective of the gatherings and the long-term infrastructure goals.

-

- Alignment: People need to do more listening and shift priorities or adjust work accordingly.

-

- Assessing progress and results: Pay more attention to measuring success, accountability, and action planning.

What the LA Community Engagement Process is Enabling: Early Results

Since 2019, the Sewall Foundation has partnered with LA on shifting from foundation-driven to community-led grantmaking, enabled by reliable, general operating funding that supports all organizations to stay involved. These years have been about relationships, learning, and incremental change. Overall, this process has made significant progress toward reaching its goals. A key success factor has been ecosystem members’ willingness to collaborate, to take responsibility, and to practice shared accountability.

We have observed some significant shifts toward community-led planning, network design, and participatory grantmaking resulting from a range of activities, participatory processes, and strategies.

-

System mapping, conducted in facilitated sessions just before the pilot period, enabled participants to see gaps, duplication, understand who is doing what, and to identify shared opportunities. Increased knowledge and awareness of each other’s work have led to increased cooperation and collaboration in the ecosystem.

-

Participatory budgeting via a virtual tool that was introduced to the ecosystem in the pilot period enabled the people doing the work to use their expertise to allocate resources to achieve common goals. Community decision-makers chose to allocate funding to collaborative infrastructure—convenors, steering committees; shared priorities—pilot projects, pooled fund for emergencies; and the existing work of collaboratives and organizations.

-

Community grantmaking, used to allocate funds to priority projects, enabled grantee partners to create fair, participatory processes for funding special projects. In this way, decision-making and accountability is shifting from Sewall to the ecosystem. Ecosystem members have successfully created grant funding criteria and processes for prioritizing projects; in fact, their work was a model for guiding funding allocation criteria following the mass shooting in Lewiston in October 2023. Ideally, ongoing management of the funds shifts to the community as well via a “fiscal host” organization. The fiscal host model has been more challenging to implement due to the varying capacity of community organizations for the administration of grant disbursement and management.

-

Community goal setting, begun in 2023-2024, will enable the ecosystem to clarify its collective work, roles, strategic priorities, and how it will measure progress.

-

The design of governance structures enabled ecosystem members to select the collaborative structure that would best enable them to meet their goals. Following a commonly agreed-upon protocol, members of each priority area selected different structures to meet their needs. The structure in each priority area looks quite different, spanning loose network (Health and Food Systems) to a formal collaborative (housing). As one network partner put it: “We want resources moving and action happening, but with a light touch structure for coordination” - Health and Food Systems partner.

-

Alternative reporting enabled ecosystem members to share what they are most proud of with each other. In its efforts to live up to its commitment to trust-based philanthropy, Sewall has been experimenting with alternatives to the traditional grantee report. In April 2024, ecosystem participants each created 1-2 slides to share their accomplishments with each other in virtual gatherings. Grantees were invited to take a “gallery walk”, to ask questions, and to reach out to each other for further information. Member feedback suggests that this activity helped people learn more about each other’s work, spur deeper communication across organizations, and generate new ideas.

Below, we share outcomes associated with each priority area, focusing on outcomes related to building capacity, supporting collaborative, and systems-focused work.

Community Health and Wellness and Food Systems

This very diverse group became the hub for a wide range of health-related work in LA, from food systems to early childhood, mental health and substance use, to the arts and aging. The self-governing model they chose was to remain in a loose network with a central communication hub to promote better coordination and collaboration across the network. During the pilot period, they have accomplished a great deal:

-

- Conducted participatory budget allocation for Community Health and Food Systems budgets.

-

- Defined a collaborative structure of a network.

-

- Participants chose a local public health organization to develop the communication hub. Led by staff who were willing to adapt to group needs, they started with a newsletter that evolved into a website. They have also hosted an in-person convening.

-

- As part of its resource allocations in 2024, a smaller working group designed a “Health and Wellness Shared Opportunities Fund” that ecosystem partners can access on behalf of a client experiencing an emergency. The group set eligibility criteria, individual grant amounts, and reporting requirements. The fund has successfully allocated over $40,000 in funds to people in need. A local community-based organization serves as the fund administrator.

-

- Created space to build awareness of each other’s work and discuss the response to the impacts of gun violence in Lewiston.

Figure 6: Ecosystem structure for Community Health & Food Systems

Housing

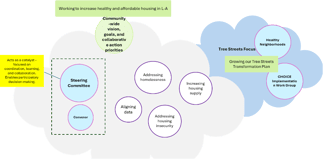

This priority area encompasses the whole housing continuum, from emergency services for people who are unhoused to shelters, subsidized and supportive housing, to affordable and safe housing, to home ownership. Members of this group reached consensus that a representative governance structure would best serve their needs for hiring a convener, information gathering/synthesis, facilitation, and advocacy.

Figure 7: L-A Housing Alliance Plan-on-a-Page

-

- Selected a collaborative as their structure, stewarded by a Steering Committee and a convener.

-

- The Steering Committee created bylaws, a convener job description, and hired a convener who was housed at a local grassroots organization.

-

- Conducted participatory funding allocation for housing budget in 2023 and 2024.

-

- Mapped the local housing continuum (people who are unhoused to advancing home ownership), resulting in a better understanding of local resources and gaps.

-

- Developed a Plan-on-a-page and work plan for the housing ecosystem.

-

- Facilitated a community granting process for priority projects supporting work across the housing continuum, from shelters to home ownership.

Figure 8: L-A Housing Alliance Structure

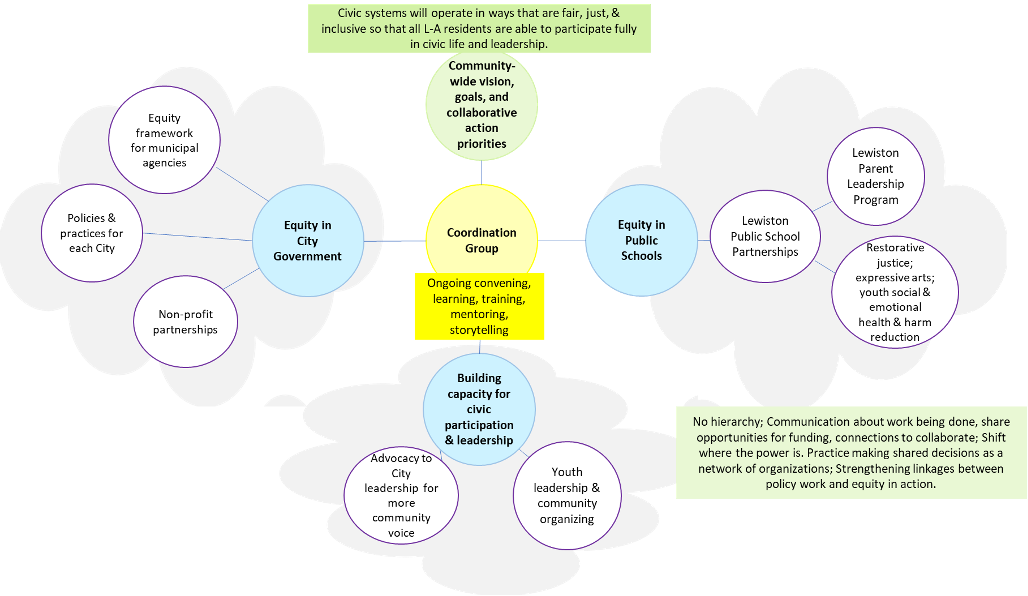

Equity in Civic Systems

This priority area seeks to promote equity in municipal agencies as well as in the school system, with an emphasis on youth engagement and leadership in schools. Its overall vision is that municipal systems will operate in ways that are fair, just, and inclusive of all LA residents, who are able to participate fully in civic life and leadership.

-

- Completed participatory funding allocation for ecosystem budget in January 2023.

-

- Supported Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion positions for the Cities of Auburn and Lewiston, and for City Spirit.

-

- Supported Lewiston Public School to formalize partnerships for initiatives focused on parent and youth leadership, restorative justice, and social and emotional health.

-

- Allocated shared funds for a representative Coordination Group to design and convene an in-person Equity Summit in December 2024, focused on elucidating challenges and opportunities and begin development of a community-wide action plan.

-

- The group began updating its structure and shared priorities at the end of the pilot period. In 2025, this work will continue, as well as its support for BIPOC- and youth-led organizations to work collectively.

Figure 8: Ecosystem structure for Equitable Civic Systems

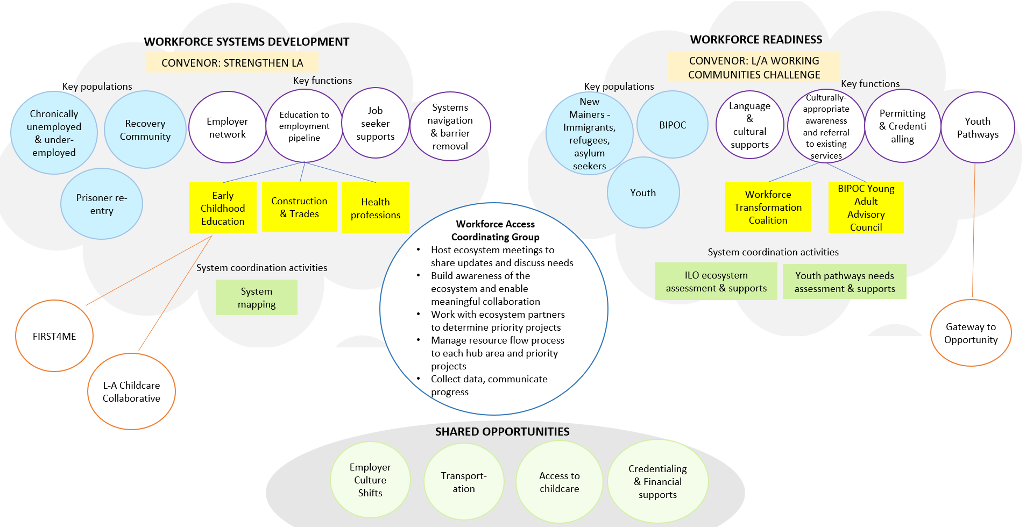

Workforce

Priorities for this area include creating better pathways for job seekers and employers to reach each other and together build a stronger workforce; and increasing opportunities for youth and BIPOC to train for, find, and succeed in the workforce. A primary goal for this group is to better coordinate numerous efforts across the region.

|

A Success Story: A Sewall-funded pilot program on recovery-friendly workplaces catalyzed the implementation of 7 recovery-friendly workplaces in LA, which was then leveraged into “Recovery Friendly Workplace Maine.” Workforce members attribute this success to Sewall’s seed funding. (Mark LeFebre) |

-

- Selected Decentralized Collaboration as their collaborative approach, comprised of two convening organizations and a coordination group to ensure communication and coordination across the network.

-

- Participatory budget allocation for the pilot period budget.

-

- Budget was allocated for cross-cutting shared priorities, including a transportation pilot, a recovery-friendly workplaces pilot, access to childcare, and credentialing and financial support.

-

- Created space to build awareness of each other's work and discuss issues that impact workforce access.

-

- Launched a collaborative effort to improve coordination of diverse childcare providers and improve access to childcare for families regardless of income. The early childhood collaborative received facilitation support to form and was then able to receive State funding for its work.

-

- Defined a structure for the ecosystem of partners: Decentralized Collaboration. The ecosystem will have two convening organizations with a coordinating sub-group focused on bridging the ecosystem, prioritizing shared opportunities, and managing resource flows to each hub area.

-

- Defined representation criteria for the coordinating sub-group and recruited members (Aug 2024-Dec 2024).

Figure 8: Ecosystem structure for Workforce Access

Challenges, Opportunities, and Lessons Learned During the Pilot Period

While each priority area has made progress toward its goals, progress is happening at a different pace and in a different way based on its needs, goals, and context. As participants have experimented with new ways of organizing themselves, they identified a range of ongoing challenges regarding funding, funding constraints, the fiscal host role, and continuing competition among organizations that can create barriers to system improvements. The most common challenges are discussed below.

-

Balancing meeting one’s own organizational and community needs against thinking as an ecosystem has been challenging for some participants. This appears to be one of the major challenges associated with community-driven change efforts, especially when the ecosystem is comprised of many small, grassroots organizations serving communities that are marginalized. Being fully present to discuss and act on broad, system-level challenges is difficult when people are in crisis. Yet the case for network-building and systems improvement was reinforced when this network, having done the work of assessing community needs and learning what different organizations do, was faced with allocating resources in the aftermath of the Lewiston shootings. This group provided essential background information and criteria for funding to funders around Maine.

-

More work needs to be done to give youth organizations the resources they need to participate fully in the ecosystem and to feel comfortable bringing their issues into the conversation. Participants prioritized a youth leadership program and organizational capacity building as ways to better center youth. Respondents were mixed on the idea of developing a separate youth cohort.

“Technical assistance should include leadership training for youth and youth leaders, as well as training for other marginalized groups of youth that don’t fall into the BIPOC category but who are also at great risk, such as unsheltered and unaccompanied youth.” Participant

-

People felt that the needs of BIPOC-led organizations were well-represented, but were less likely to agree that BIPOC-led organizations have the resources they need to fully participate in the process. The most frequently mentioned idea for better centring BIPOC-led orgs and leaders was capacity building, followed by more support for leadership development, especially for young leaders.

-

One of the original priorities set by participants in this process was to reduce competition in the network of nonprofits in LA. This has worked remarkably well, as evidenced by numerous examples of collective decision-making about resource allocation. Yet competition among organizations remains, particularly when they are serving (or want to serve) the same communities, or when they fear losing current funding.

-

Toward the end of the pilot period, there may have been too much emphasis on process versus action. While a major goal of the pilot was to build structures and processes, the team may have focused too heavily on this as opposed to shared goal setting.

-

LA is blessed with a comprehensive non-profit ecosystem, but a proliferation of small, nascent organizations has led to some duplication of effort and resources spread thin. There are indications that the ecosystem partners are recognizing duplication as a problem and are considering this in their funding decisions (e.g., setting criteria for exclusion if the work is duplicative or not aligned with existing efforts).

Observations on Sewall’s Approach

The Sewall Foundation has forged a new, collaborative way to build partnerships to live up to its commitment to trust-based philanthropy and to meet the needs of the community in the Lewiston-Auburn area. They have also brought an innovative approach to grant-making, making it much more collaborative and community-focused.

People in the LA ecosystem shared what has worked well for them regarding this experience. They loved how inclusive the process has been, especially with its attention to youth-led and BIPOC-led organizations. Consistent, transparent communication and regular convenings are greatly appreciated. Sewall has fostered a “culture of possibilities” that gives meaning to the idea that communities are able to make their own choices, collectively, about how change will occur. People also praised Sewall’s flexibility around reporting and ease of applications.

This has been “a conscious effort to bring diverse voices to the table that gives small, BIPOC-led organizations an equal voice.”

Participant

One key lesson out of the pilot period is that small grants do not enable transformative change. Rather than making larger grants, Sewall created an inclusive process whereby every organization would receive seed funding. The ecosystem grew large, so individual grants remained relatively small. Participants appreciated the funding but observed that spreading money thinly over many organizations made it more difficult to support potentially impactful, larger grants or capacity building. Some collaborative grants have been funded that focus on systemic change; for example, a grant supporting a transportation system for shift workers and a childcare collaborative that integrates BIPOC-led and mainstream organizations.

The Sewall team also struggled at times regarding how prescriptive to be and how to use its power in service to community goals. Having one person, the Sewall community partner, holding all the organizations and partners in a very relational way was hard to maintain and sometimes delayed progress. As the community assumes more of a primary governance role, this should be less of an issue.

Sewall has learned that managing a large, complex ecosystem of organizations with multiple priority areas (all with unique grant processes as determined by the community) has become increasingly challenging. The complexity of the ecosystem, the number of grants, and new, participatory grantmaking and fiscal host processes have put strain on Sewall’s grants management staff.

Another lesson learned is that shifting power to communities can add burden to stretched organizations. The idea of transferring funds to an organization to manage was more complex than anticipated. Particularly when the role involves integrating a new hire, the employee needs to be located in an organization that can not only make payroll, but also provide support, supervision, and thought partnership. It became clear that if organizations are to take over administrative, grants management, HR, and fiscal responsibilities from a foundation, they must have the capacity to do so or the assistance of the funder to build this skill set.

There are indications that participants in the community engagement process recognize that to make a greater impact, they need to reconsider how resources are allocated. As funding is limited, some participants called for having an honest conversation about funding constraints and how to meet increasing needs in the community while being impactful. It is anticipated that the community goal-setting process will help each priority area determine which kinds of grants, to which combination of organizations, will best help them reach their agreed-upon goals.

In parallel with the community’s goals, Sewall hopes that funders will work even more closely together to support the advancement of community-led goals. One story demonstrates the promise of a collaborative funder effort in LA:

In October 2023, a mass shooting in Lewiston brought the community together to provide emergency response and other collective funding to respond to community trauma and healing. Because this diverse ecosystem with experience in participatory resource allocation was already in place, MPC, Maine Community Foundation, and LA funders met to identify community priorities with input from community partners. Participants were invited to add to the Listening document on short, mid-, and long-term needs that funders then used as a shared resource. Having the ecosystem in place helped funders react more quickly and responsively to the crisis.

Anticipating 2025 and Beyond

We are transitioning from the pilot to the next phase of our collaborative process, which Sewall will continue supporting with multi-year funding, convenings (until the community can take them over), focused support for emerging collaborative structures and capacity building for organizations. The foundation has begun to step back from implementing the process to support more community-centred leadership. The success of this shift is reliant on community leaders, emphasis on relationship building, readiness, and the belief that coordination is needed to address systemic gaps.

Lauress Lawrence, Sewall’s longtime LA community partner, shared her reflections at the end of the pilot period, paraphrased below:

Emergent learning is a commitment and has helped the process develop organically without a strict playbook. Now, we are shifting the focus to the community, and away from Sewall— “this is your work.” You’ve all been growing the equity lens, including centring youth. Having built strong relationships and trust (mostly), it’s time to shift to changing systems via big, bold ideas.

Sewall’s goal is to continue to support community-led dialogue and coordination and decision-making, such that funding from Sewall and other funders is responsive to community priorities. Sewall hopes that LA partners will benefit from larger, multiyear grants to create more transformational change. Sewall remains committed to ongoing communication with LA priority groups and has the flexibility to adapt to emerging community-identified needs and approaches. In the meantime, Sewall has committed five more years of funding to LA.

In January 2025, participants identified the following action steps for the ecosystem over the next three years.

Considerations for 2025 – 2028

2025

-

Keep working on developing trust within the ecosystem.

-

Continue building healthy collaborative structures to coordinate and sustain the work.

-

Work more intentionally on developing coordinated efforts to shift systems. To do so, the group should ask “What will be different 3 years from now if we work together?” and discuss and name systems-focused projects which will be funded for the subsequent 3 years.

-

Develop a framework and strategy for youth engagement and supporting young leaders.

2026-2028

-

Implement community-led, systems-focused action for impact.

-

Continue to provide funding for community-based collaborative structures and community-led strategic partnerships to shift systems towards equitable outcomes.

As this process continues into its maturity, questions remain that will be answered through continued emergent learning:

-

Having observed in the pilot phase that funding over 70 organizations spread resources thin and limited transformative work, what would funding fewer organizations make possible, for whom?

-

If fewer organizations receive funding, who will benefit, and who will be harmed? How will that affect participation in the ecosystem?

-

Sewall has reimagined its capacity-building program to be more responsive to organizations around Maine and in Lewiston-Auburn. Is it possible that these resources could contribute to organizational capacity building and leadership development in a way that would be more impactful than in the past?

-

What staff and structures will enable Sewall to support LA to move from “on the edge of independence” to a self-sustaining, functional network?